Georgia’s New Election Code: Assessment of Key Amendments

Executive Summary

On 17 December 2025, the Parliament of Georgia adopted a new Election Code without the participation of opposition parties, civil society organizations, or sectoral experts. A significant share of the substantive amendments is tailored to the narrow interests of the ruling party and raises the following major concerns:

- Abolition of out-of-country voting: For parliamentary elections, polling stations will now be opened exclusively within the territory of Georgia. As a result, Georgian citizens residing abroad have been effectively deprived of the right to vote, contrary to established international practice.

- Inequality of electoral districts: For municipal elections, the boundaries of single-member districts were fixed based on the situation as of 2025. This results in significant disparities in the power of votes and constitutes a violation of the principle of equal suffrage.

- Reduction of deadlines: The deadline for registering observers, media representatives, and representatives of electoral subjects has been changed from no later than five days before election day to no later than ten days prior, creating serious technical and logistical challenges for relevant organizations.

- Stricter rules on expulsion from polling stations: A person expelled from a polling station will be prohibited from entering any other polling station on the same day (except for voting purposes). An “electronic database of expelled persons” will be created, raising concerns about potential misuse of this mechanism against observers.

- Abolition of voter information cards: Election commissions are no longer obliged to distribute voter information cards, creating obstacles for citizens with limited access to the internet or digital technologies.

- Ban on nominating non-party candidates: Political parties are prohibited from nominating candidates who are not members of the same party.

- Single-handed dismissal of complaints: Chairpersons of election commissions are granted the authority to leave complaints unexamined unilaterally, without collegial consideration by commission members.

- Ban on audio monitoring: Audio monitoring at polling stations has been prohibited, which may complicate the collection and documentation of evidence of violations.

On 17 December 2025, the Parliament of Georgia, in the third hearing, adopted an entirely new Election Code, along with related amendments to the following legal acts: the Organic Law of Georgia “On Referendum,” the Local Self-Government Code, the Law “On the Development of Highland Regions,” and the Rules of Procedure of the Parliament of Georgia.

According to the authors of the draft law, since the adoption of the Election Code on 27 December 2011, approximately 100 amendments had been introduced at various times, and a significant portion of the existing text consisted of transitional provisions that had lost their relevance. Consequently, the authors argued that adopting a new Election Code was necessary, with the stated aim of refining relevant provisions of the organic law, clarifying certain procedures, systematizing homogeneous norms, and simplifying their interpretation. However, alongside technical amendments and the systematization of norms, the new Election Code introduced fundamental changes that substantially altered the previous legal framework in several matters. In this document, the International Society for Fair Elections and Democracy (hereinafter - ISFED) reviews and assesses the key amendments introduced by the new Election Code.

1. The Legislative Process

Any significant legislative amendment requires the involvement of relevant stakeholders and reasonable timeframes. However, in recent years - particularly following the 2024 parliamentary elections - it has become common practice for major legislative changes to be adopted through an exclusive process, without any formal consultations with stakeholders, including sectoral specialists. As a rule, such amendments are tailored to the narrow partisan interests of the Georgian Dream. The process of adopting the new Election Code also turned out to be a continuation of this trend.

The legislative amendments were initiated on 12 November 2025 by nine Georgian Dream members of parliament. The explanatory note explicitly states that no consultations were held during the drafting process. During parliamentary hearings, none of the major opposition parties, civil society organizations, or field experts were involved.

2. Description and Assessment of Key Amendments

2.1. Abolition of Out-of-Country Voting

Under the new Election Code, Georgian citizens are no longer able to vote abroad. Similar to municipal elections, parliamentary elections will now be conducted exclusively within Georgia’s state borders. One of the arguments cited for this change was the non-mandatory nature of special electoral measures.

Although traditional interpretations of electoral rights do not require states to ensure voting for citizens residing abroad, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), in its 2005 resolution, emphasized that electoral rights constitute the foundation of democratic legitimacy and the representative nature of the political process, which should evolve toward inclusive democracy in line with societal progress. According to the PACE, priority should be given to ensuring effective, free, and equal electoral rights for the largest possible number of citizens, including due consideration of the voting rights of citizens living abroad. The PACE recommends that Council of Europe member states grant their citizens residing abroad the right to vote in national elections and take appropriate measures to facilitate the effective exercise of this right.

Furthermore, the Venice Commission has called on states to adopt a positive approach toward the voting rights of citizens residing abroad, considering European mobility and the specific circumstances of certain countries, as this right contributes to the development of both national and European citizenship.

In modern societies, the provision of both active and passive electoral rights to citizens residing abroad is widespread, with states employing special voting arrangements to facilitate participation. According to data from the International IDEA, more than 150 countries allow their citizens to vote abroad, including almost all Council of Europe member states. Moreover, the global trend toward facilitating out-of-country voting continues to grow, with voting methods extending beyond in-person voting (42% of countries) to include postal (20%) and electronic voting (6%).

In light of the above, ISFED considers the abolition of out-of-country voting for Georgian citizens to be contrary to good international electoral practice and global trends. It clearly creates the impression that this step, taken against the principle of universal suffrage, is motivated solely by the narrow partisan interests of the Georgian Dream. Notably, in the 2024 parliamentary elections, the Georgian Dream party received approximately 13% of the vote at polling stations opened abroad, while it secured around 54% nationwide, according to the results announced by the Central Election Commission.

2.2. Regulation of the Creation of Electoral Districts and Local Single-Member Districts

The new Election Code consolidated, largely within a single chapter, the provisions regulating the creation of electoral districts and local single-member districts. A significant change concerns the basis and deadlines for establishing single-member districts for municipal representative body elections. As with the 2025 municipal elections, the Central Election Commission (CEC) and district election commissions are required to establish local majoritarian districts for municipal council elections, taking into account the territorial and administrative characteristics of the respective self-governing unit, no later than 1 July of the election year.

At the same time, provisions defining the composition of municipal councils and the rules for delimiting electoral districts - which previously allowed for adjustments in the number of majoritarian seats and district boundaries in response to changes in administrative units or voter numbers - were removed from the Code. Instead, a new provision stipulates that for elections to the Tbilisi City Council and other self-governing cities, the CEC and district election commissions shall establish local single-member districts based on the configuration of majoritarian districts determined for the 2025 municipal elections.[1]

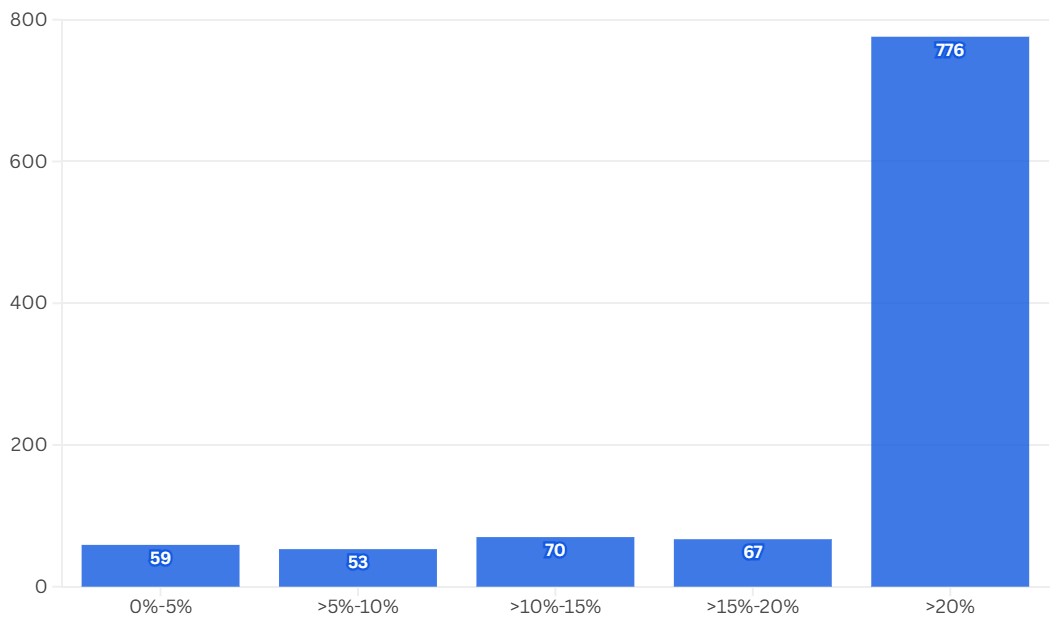

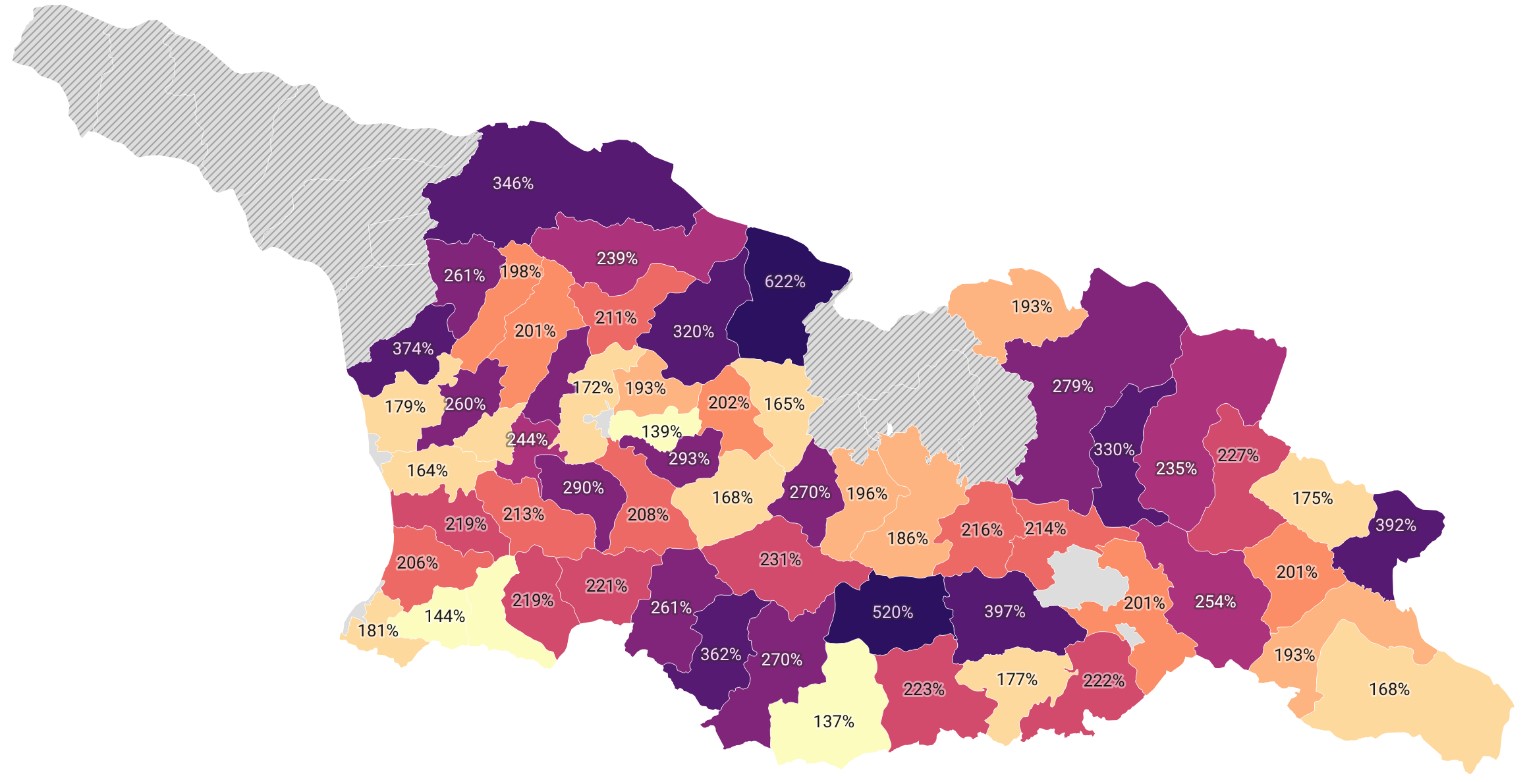

Maintaining the majoritarian districts established for the 2025 municipal elections unchanged for all subsequent municipal elections violates the fundamental principle of equal suffrage enshrined in international treaties, European electoral standards, the Constitution of Georgia, and the Election Code itself. In 2025, the number of voters across single-member districts within municipalities was distributed in a highly unequal manner, resulting in a gross violation of the principle of equal voting power. Notably, in 82% of the single-member districts created in 2025, the deviation from the municipal average number of voters exceeded 15% (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

According to the Venice Commission’s Code of Good Practice in Electoral Matters, the maximum permissible deviation from the established criterion depends on the specific context, but should rarely exceed 10% and never surpass 15%, except in exceptional circumstances. The most recent delimitation of single-member districts for local representative bodies in Georgia not only exceeds permissible limits but, in the vast majority of municipalities, surpasses critical thresholds, with deviations reaching several hundred percent in some cases.

Figure 1. Deviation from the average number of voters in single-member districts of self-governing communities

Note: Deviations are calculated based on the number of registered voters in each municipality’s single-member districts as of 17 September 2025.

Under such conditions of extreme inequality, voters registered in larger districts are placed at a disadvantage compared to those in smaller districts. It is noteworthy that, in 2016, the Constitutional Court of Georgia declared the existence of unequal electoral districts in parliamentary elections unconstitutional. According to the Venice Commission’s Code of Good Practice, the requirement of equal voting power applies to national, regional, and local elections alike. Therefore, violations of this right under the Election Code should be considered unconstitutional.

Figure 2. Overall range of deviations from the average number of voters in single-member districts across municipalities

2.3. Changes to Registration Deadlines for Representatives of Electoral Subjects, Observers, and Media

The new Election Code shortened the deadline for domestic observer organizations to submit applications for observer registration. Previously, organizations could submit applications no later than five days before election day; this deadline has now been extended to no later than ten days before election day. A similar change applies to accreditation deadlines for representatives of the press and other mass media outlets. The same ten-day deadline has been introduced for the appointment, withdrawal, and replacement of representatives of electoral subjects, whereas previously such actions were permitted up to and including election day.

ISFED believes that these shortened deadlines compel all types of organizations to finalize the mobilization of human resources for election observation or coverage prematurely, thereby limiting their operational and logistical flexibility. Election preparation is a dynamic process, and the mobilization and replacement of personnel often continue until the final stages. Reducing these deadlines may therefore constitute a significant impediment. Moreover, the risk increases that, in cases of pressure exerted on observers or representatives of electoral subjects, timely replacement will no longer be possible. The explanatory note to the draft law failed to justify the legitimate aim served by these changes.

2.4. Expulsion from Polling Stations

The new Election Code amended the rules governing expulsion from polling stations on election day. A person expelled from a polling station will be prohibited from entering any other polling station on the same day, except for voting. To this end, the election administration will maintain records of expelled individuals.

Specifically, in cases of obstruction of the work of a precinct election commission or disruption of order on election day, the precinct election commission decides on the expulsion of the violator from the building where the commission is located, drawing up a formal act signed by the chairperson and commission members. The act records the violator’s name and surname, the district and precinct numbers, the nature of the violation, and the exact time of its commission. An expelled individual is prohibited from entering or remaining in any polling station or polling premises on election day, except for voting. The election administration maintains an electronic database of expelled persons for verification purposes.

ISFED believes that this amendment disproportionately and unreasonably restricts the rights of persons entitled to be present in polling stations and, given Georgia’s context, carries a high risk of abuse of this punitive mechanism.

During the 2024 parliamentary elections, local and international observer organizations reported incidents of verbal abuse, physical violence, expulsion from polling stations, threats, and pressure against observers by election commission members, representatives/coordinators of Georgian Dream, and so-called fake observers. In many cases, observers were denied the opportunity to monitor voter verification procedures. There were instances where observers were expelled from polling premises for requesting the identification or remedy of violations. In some cases, commissions did not allow observers to monitor voter verification at all. Notably, commission members and party representatives/coordinators displayed aggression and hostility toward observers.

2.5. Abolition of the Obligation to Distribute Voter Information Cards

The new Election Code removed the obligation of precinct election commissions to distribute voter information cards.[2] According to the explanatory note, due to the development of information technologies and the diversity of voter information channels, informing voters through such cards is no longer deemed necessary.

ISFED considers this amendment problematic for certain groups, particularly those with limited access to modern technologies and internet resources - whether due to insufficient internet coverage or lack of digital skills. Under such conditions, especially when polling station locations change, the lack of information may pose a significant obstacle to voters and threaten the full exercise of their electoral rights.

2.6. Prohibition on the Nomination of Non-Party Candidates by Political Parties

Under the new Election Code, political parties are prohibited from nominating as candidates individuals who are not members of the respective party. Before the entry into force of the new Code, political parties could nominate any individual who was not a member of another political party. This amendment applies to the submission of party lists in parliamentary elections, as well as to the registration of mayoral candidates, majoritarian candidates for municipal councils, and party lists in municipal elections.

For registration purposes, the political party must submit to the election commission or its chairperson, no later than 30 days before election day, a completed and signed declaration by the candidates confirming their membership in the nominating party. If the candidate left another political party within the six months preceding the submission of the registration application, the declaration must include the exact date of departure and the name of the former party. Failure to meet these requirements results in the candidate’s non-registration or the cancellation of an already registered candidate by decision of the chairperson of the relevant election commission.

2.7. Adoption of Decisions to Leave Complaints Unexamined

Under the previous version of the Election Code, the central and district election commissions were collectively authorized to review election-related applications and complaints, including decisions to leave complaints unexamined where appropriate. The new Election Code grants the authority to decide on leaving a complaint unexamined unilaterally to the chairperson of the relevant election commission, instead of requiring collegial consideration by commission members.

While the explanatory note states that the chairperson should examine the admissibility of complaints and make relevant decisions, it does not justify the necessity of assigning this authority exclusively to the chairperson.

The practice of chairpersons unilaterally reviewing alleged violations of electoral legislation was critically assessed by the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODIHR) Election Observation Mission during the 26 October 2024 parliamentary elections. In its final report, the Mission noted that the majority of complaints submitted to the election administration were reviewed by the chairpersons of the CEC or district election commissions, undermining the collegial nature of these bodies and negatively affecting transparency. Of the 231 complaints submitted before election day, only 25 (11%) were reviewed at public hearings.

2.8. Ban on Audio Monitoring During Photo and Video Recording at Polling Stations

The new Election Code explicitly states that photo and video recording at polling stations does not include audio monitoring. The initiators of the draft law linked this change to the protection of personal data. However, the explanatory note does not substantiate what additional risks to personal data protection arise specifically from audio monitoring. Moreover, the concept of “audio monitoring” remains unclear, as does its distinction from video monitoring and the mechanisms for enforcing such a ban.

Previously, photo and video recording at polling stations was regulated by CEC Decree No. 42/2012 of 24 September 2012, which established rules ensuring that recording was conducted without unlawful processing of personal data. Under that decree, from the arrival of the first voter until the last voter cast their ballot, persons entitled to be present in polling premises were permitted to conduct photo and video recording, including with audio monitoring, provided that it did not interfere with the voting process.

ISFED considers audio monitoring, in certain cases, to be a decisive method for documenting violations. In its absence, reliable recording and subsequent contestation of many types of electoral violations becomes impossible. Amendments justified by personal data protection may thus be used as a tool to restrict the activities of observer and media organizations, reducing their ability to collect evidence.

[1] Organic Law of Georgia “Election Code of Georgia”, Article 144. Composition of the Municipal Representative Body – the Sakrebulo

[2] The voter card indicated the following information: the date and time of voting; the address of the polling station (including the floor and room numbers); the voter’s number on the voters’ list; the number of the electoral precinct; the voter’s surname, first name, date of birth, and place of registration.